The Day the Bank of England Admitted They Were Wrong

In 2014, something remarkable happened. The Bank of England – one of the most powerful financial institutions in the world – published a statement that turned everything we thought we knew about money upside down.

“Most of the money in circulation is created, not by the printing presses of the Bank of England, but by the commercial banks themselves,” they wrote. “Banks create money whenever they lend to someone in the economy or buy an asset from consumers.”

This might sound boring to most people. But for David Graeber, the anthropologist who wrote “Debt: The First 5000 Years,” it was like winning the lottery. As he put it in his book’s afterword: “I must admit my first reaction was to pop a bottle of champagne on behalf of anthropologists everywhere: after a century’s work, we may well have finally managed to do it.”

What had they “done”? They had finally gotten one of the world’s most important banks to admit that everything we learned in school about money was basically a fairy tale.

For over a hundred years, economists have been telling us the same story: Long ago, people used to barter – trading chickens for shoes, grain for tools. But bartering was difficult, so they invented money to make trading easier. Banks then collected this money from savers and lent it out to borrowers.

The problem? This story is completely made up. And now even the Bank of England was admitting it.

The Real Story: How Banks Actually Create Money

To understand why this matters, we need to go back to where it all started. Graeber traces the modern banking system to a scheme that was “originally pioneered by the Bank of England” centuries ago.

Here’s how it really works: When a government needs money (usually to fight wars), the central bank doesn’t actually lend them gold or existing money. Instead, they create new money out of thin air by buying government bonds. It’s like writing an IOU and then treating that IOU as if it were real money.

The Bank of England did this first. The American Federal Reserve copied the same system. As Graeber explains: “The difference is that while the Bank of England originally loaned the king gold, the Fed simply whisks the money into existence by saying that it’s there.”

Think about that for a moment. The money in your wallet exists because a bank somewhere decided it should exist. There’s no pile of gold backing it up. There’s no ancient history of barter that led to it. It’s just numbers on a computer screen that we all agree to treat as real.

This bothered people like Thomas Jefferson, who saw it as “the ultimate pernicious alliance of warriors and financiers.” He understood that when banks can create money to lend to governments, and governments use that money to fight wars, you get a system where war and debt feed off each other.

1971: The Year Everything Changed

The story gets more interesting – and more troubling – when we jump to August 15, 1971. That’s when U.S. President Richard Nixon made an announcement that changed the world forever.

Until then, other countries could exchange their U.S. dollars for gold. Nixon ended this system. Why? Because America was spending too much money bombing Vietnam.

Graeber doesn’t mince words about this: During 1970-1972 alone, Nixon “ordered more than four million tons of explosives and incendiaries dropped on cities and villages across Indochina,” earning him the nickname “the greatest bomber of all time” from one senator.

All those bombs cost money. More money than America had. So Nixon did something that sounds almost unbelievable: he turned the entire world’s money system into a way to pay for American wars.

Here’s how it worked: After 1971, countries couldn’t exchange their dollars for gold anymore. But they still needed dollars to buy oil and trade with each other. So they had to keep lending money back to America by buying U.S. government bonds. It was like being forced to lend money to the person who was bombing your neighbors.

As Graeber puts it: “Behind the wizard, there’s a man with a gun.”

The Military Machine Behind Your Money

This isn’t just ancient history. Today, the American military has about 800 bases around the world. The U.S. spends more on its military than all other countries combined. And according to Graeber, this isn’t a coincidence – it’s what keeps the whole money system working.

Think about it this way: Why do countries around the world still use dollars for trade? Why do they keep lending money to America by buying U.S. government bonds?

Graeber’s answer is simple: because America has “the ability, through roughly 800 overseas military bases, to intervene with deadly force absolutely anywhere on the planet.” The U.S. can “drop bombs, with only a few hours’ notice, at absolutely any point on the surface of the planet.”

When countries have tried to challenge this system, things haven’t gone well for them. Saddam Hussein switched from dollars to euros for oil sales in 2000. Iran did the same in 2001. Both countries were soon facing American bombs.

Meanwhile, countries that play along with the system – like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan – get to host American military bases and buy American weapons. It’s protection money on a global scale.

Even China, America’s biggest rival, plays this game. They lend money to America by buying U.S. bonds, which helps fund the American military that’s supposedly containing China. Why would they do this?

Graeber has a fascinating answer: China has been playing this game for thousands of years. Throughout Chinese history, the empire would shower neighboring countries with gifts and luxuries, making them dependent and lazy. “It was such wise policy that the U.S. government, during the Cold War, more or less had to adopt it” to contain China. Now China is doing the same thing back to America.

How Debt Became a Moral Issue

But there’s something even more disturbing about our debt-based system: it has changed how we think about right and wrong.

Graeber noticed that in America, there are basically two different moral systems around debt. For the rich, debt is creative and godly. For everyone else, debt is sinful and shameful.

In the 1980s, a writer named George Gilder argued that rich investors creating money out of nothing was actually imitating God’s power to “create something out of nothing.” Televangelist Pat Robertson called this “the first truly divine theory of money creation.”

But for ordinary people, debt became the new original sin. As Canadian writer Margaret Atwood observed, “Debt is the new fat.” Instead of worrying about being attractive, people now panic about debt collectors.

There are even “debt TV shows” that work like religious revivals: tearful confessions by people who spent too much, stern lectures from hosts playing the role of priests, moments of “seeing the light,” cutting up credit cards as penance, and finally – if you’re lucky – forgiveness and redemption.

But here’s what these shows don’t tell you: Most people don’t go into debt because they’re buying luxury items. The biggest cause of bankruptcy in America is medical bills. Most debt comes from just trying to survive – needing a car to get to work, going to college, or helping family members.

As Graeber puts it: “One must go into debt to achieve a life that goes in any way beyond sheer survival.”

The Bangladesh Story: When Good Intentions Go Wrong

This moral confusion around debt isn’t just an American problem. Graeber tells the story of how it spread around the world through something called “microcredit” – and this story hits close to home for those of us from Bangladesh.

In the 1990s, the world fell in love with the Grameen Bank’s idea of giving small loans to poor people, especially women, to start tiny businesses. The bank’s founder said “Credit is a human right.” It sounded beautiful and empowering.

The idea spread everywhere. International organizations started pushing microcredit as the solution to poverty. As one NGO consultant told an anthropologist in Cairo: “Money is empowerment. This is empowerment money… It should be the same thing here, why not help them get into debt? Do I really care what they use the money for, as long as they pay the loan back?”

Notice something disturbing in that quote? The goal wasn’t actually to help people escape poverty. The goal was to get them into debt. Debt itself had become the point.

And just like the American housing crisis, the microcredit boom eventually crashed. “All sorts of unscrupulous lenders piled in, all sorts of deceptive financial appraisals were passed off to investors, interest accumulated, borrowers tried to collectively refuse payment, lenders began sending in goons to seize what little wealth they had (corrugated tin roofs, for example).”

The result? “An epidemic of suicides by poor farmers caught in traps from which their families could never, possibly, escape.”

What started as “credit is a human right” became a system that literally drove people to kill themselves.

The Cycles of False Hope

Graeber sees a pattern in how these debt systems work. Since World War II, he identifies two major cycles:

First cycle (1945-1978): People demanded basic rights – civil rights, workers’ rights, women’s rights. The system responded by giving some people (mostly white workers in rich countries) a deal: you can have unions, pensions, healthcare, and your kids can go to college. In return, stop talking about revolution.

Second cycle (1978-2008): More people wanted in on that deal. But instead of extending real benefits to everyone, the system offered something different: debt. You can’t have a guaranteed pension, but you can have a 401(k) account to gamble in the stock market. You can’t have free healthcare, but you can have credit cards to pay medical bills. You can’t afford college, but you can take out student loans.

As Graeber puts it: “Rather than euthanize the rentiers, everyone could now become rentiers” – meaning everyone could try to make money from money, instead of from actual work.

But there was a catch: “buying a piece of capitalism” for most people “slithered undetectably into something indistinguishable from those familiar scourges of the working poor: the loan shark and the pawnbroker.”

The system promised that everyone could become a mini-capitalist. In reality, it turned everyone into debtors.

The Violence Behind the Numbers

Why does this keep happening? Graeber’s answer goes to the heart of what money really is.

He argues that markets didn’t develop naturally from people trading with each other. Instead, they came from violence – from slavery, conquest, and theft.

Think about it: “Who was the first man to look at a house full of objects and to immediately assess them only in terms of what he could trade them in for in the market likely to have been? Surely, he can only have been a thief.”

Soldiers looting cities, slave traders selling people, debt collectors seizing property – these were the first people to see the world as just a collection of things with price tags.

This violent origin never really went away. “Any system that reduces the world to numbers can only be held in place by weapons, whether these are swords and clubs, or nowadays, ‘smart bombs’ from unmanned drones.”

But there’s something even deeper going on. Graeber argues that debt systems don’t just use violence – they “continually convert love into debt.”

What does he mean? Think about all the ways we care for each other that can’t be measured: parents raising children, friends helping friends, communities supporting their members. These relationships are based on love, not calculation.

But debt systems take these caring relationships and turn them into numbers. Suddenly, what you owe your parents becomes a financial obligation. What you owe society becomes a debt that must be repaid with interest. Even what you owe to nature becomes something you can buy and sell with carbon credits.

As Graeber puts it: “By turning human sociality itself into debts, they transform the very foundations of our being – since what else are we, ultimately, except the sum of the relations we have with others – into matters of fault, sin, and crime.”

Graeber’s Vision: A World Beyond Debt

So what’s the solution? Graeber’s answer might surprise you.

First, he calls for a “Biblical-style Jubilee” – a massive cancellation of debts, both international and personal. This isn’t just about helping people who are struggling. It’s about reminding ourselves that “money is not ineffable, that paying one’s debts is not the essence of morality, that all these things are human arrangements and that if democracy is to mean anything, it is the ability to all agree to arrange things in a different way.”

Think about what happened after the 2008 financial crisis. Banks that had made terrible bets and lost trillions of dollars were bailed out with taxpayer money. Their imaginary money was treated as real. But ordinary people who couldn’t pay their mortgages? They lost their homes.

As Graeber points out: “As it turns out, we don’t ‘all’ have to pay our debts. Only some of us do.”

Second, he suggests we need to completely rethink what we mean by work and productivity. The current system assumes that the point of human life is to produce more and more stuff, growing the economy by at least 5% every year forever.

But this is impossible on a planet with limited resources. And it’s making most people miserable. Maybe instead of working more to produce more to consume more, we should work less and enjoy life more.

Graeber puts in “a good word for the non-industrious poor. At least they aren’t hurting anyone. Insofar as the time they are taking time off from work is being spent with friends and family, enjoying and caring for those they love, they’re probably improving the world more than we acknowledge.”

Maybe these people aren’t lazy. Maybe they’re “pioneers of a new economic order that would not share our current one’s penchant for self-destruction.”

What This Means for the Future

Graeber wrote his book just before the 2008 financial crisis, and he updated it after seeing how the world responded to that crisis. His conclusion? We’re living through a historical transformation as big as any in the past 5,000 years.

The current system of debt-based capitalism is destroying the planet and making most people’s lives worse. It can’t continue forever. The question is: what comes next?

Graeber admits he doesn’t know exactly what a post-capitalist world would look like. But he’s optimistic that “surprising new ideas will certainly emerge” – maybe from Iraq (which invented both interest-bearing debt and the first system to reject it), maybe from Islamic feminism, maybe from “some as yet completely unexpected quarter.”

What he’s sure about is that we need to start thinking bigger. For too long, we’ve been trapped in a false choice between “free markets” and “big government.” But both of these are just different ways of organizing the same basic system – one where a few people get to create money out of nothing while everyone else has to work for it.

The real choice is between continuing with a system based on debt, violence, and endless growth, or creating something entirely different – something based on what Graeber calls the “communism” that already exists in our daily lives.

By “communism,” he doesn’t mean Soviet-style dictatorship. He means the way we already share with our families, help our friends, and cooperate with our communities without keeping track of who owes what to whom. He means love.

The Promise We Can Make to Each Other

In the end, Graeber’s book is about promises. Real promises between real people, not the fake promises of debt contracts.

“What is a debt, anyway?” he asks. “A debt is just the perversion of a promise. It is a promise corrupted by both math and violence.”

Real promises are about relationships. They’re about trust. They’re about building a future together. Debt contracts are about power. They’re about fear. They’re about making sure some people stay on top while others stay on the bottom.

“If freedom (real freedom) is the ability to make friends,” Graeber writes, “then it is also, necessarily, the ability to make real promises. What sorts of promises might genuinely free men and women make to one another? At this point we can’t even say. It’s more a question of how we can get to a place that will allow us to find out.”

The first step is recognizing that the current system isn’t natural or inevitable. It’s a human creation, and humans can create something different.

The Bank of England’s 2014 admission was just the beginning. After a century of anthropologists trying to debunk the barter myth, they finally succeeded. After decades of economists insisting that banks just lend out existing money, even the banks themselves admitted they create money out of nothing.

If we can change how one of the world’s most powerful institutions talks about money, what else can we change?

As Graeber concludes: “In the largest scheme of things, just as no one has the right to tell us our true value, no one has the right to tell us what we truly owe.”

The world doesn’t owe the banks their profits. The poor don’t owe the rich their labor. We don’t owe the system our lives.

What we owe each other is something much simpler and much more radical: the chance to be human.

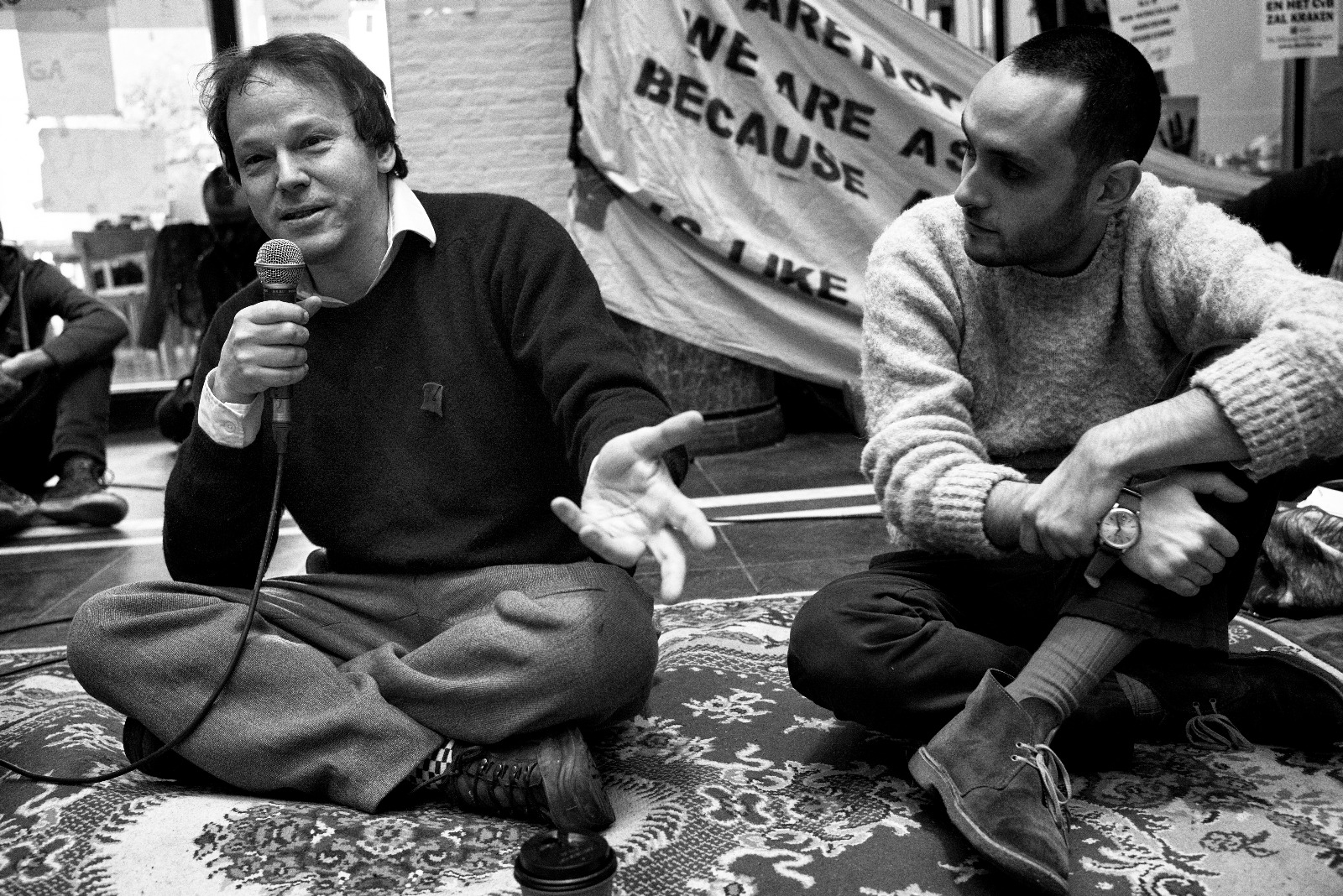

This article is based on David Graeber’s “Debt: The First 5000 Years” and draws particularly from Chapter 12 and the book’s conclusion. Graeber was an anthropologist, activist, and one of the key organizers of Occupy Wall Street. He died in 2020, but his ideas about debt, money, and human freedom continue to influence people around the world.